Red Pill, Part IV - Drones of Combat

As America apologizes for another horrific attack on Afghan civilians, we ask: what will make it stop?

Read

This week we swallow one last painful red pill and learn from the consequences of foreign interventions, nation-building efforts and forever wars. This time: how the logic of drone warfare has led to the droning on of war.

In 1905, Austrian baroness Bertha von Suttner won the Nobel Peace Prize, which she had helped convince Alfred Nobel to establish. Largely forgotten among antiwar activists, she was an outspoken critic of efforts to make combat merely less brutal. Today, Yale legal scholar Samuel Moyn finds inspiration in Suttner’s story for his own provocative stance against the logic of “humanizing” war with technological innovations like drone strikes.

International laws governing the rules of engagement in armed conflict, protecting civilians and banning torture all seem like important achievements of the 20th century. This is one reason why President Obama, aware of the public outrage over atrocities in America’s war on terror, refocused U.S. military efforts to minimize destruction, using more targeted incursions. But the choice between humane war or brutal war is a false one, Moyn argues: the real choice, and the one Americans of late been have ducking, is whether to go to war in the first place.

Meet

Samuel Moyn is a historian and the Henry R. Luce Professor of Jurisprudence at Yale Law School. His research looks at international law, human rights and political theory. Moyn writes frequently in the popular press, including essays for The New York Times and the Guardian. His most recent book is Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War (Macmillan, 2021). Follow Moyn on Twitter @samuelmoyn.

Though he ran as an antiwar candidate, Barack Obama expanded the war on terror, and his successor carried that torch, as Moyn writes in a recent piece in the Guardian.

According to Moyn, the public has come to accept persistent hostilities in part because humanitarian groups have successfully convinced military leaders to abide by the rules of war.

This paradox is a key issue he takes up in Humane, which unearths the arc, and the tensions, of humanitarian movements since the mid-1800s.

Before writing War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy saw the horrors of combat up close as an artillery officer in Crimea, and recognized the contradiction inherent in humanizing war. In 1855 he published three stories about that experience under the title Sevastopol Sketches, and they put him on the literary map. Moyn revisits their message in this Plough Quarterly essay.

Learn

As Moyn tells Will and Siva on this episode, U.S. political and military officials decided early on that international laws on initiating and carrying out war did not apply to operations against terrorist organizations.

Among the more horrific outcomes of this logic was the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq by U.S. officials and contractors.

Targeted killings were supposed to obviate cruelty at places like Abu Ghraib and the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. No prisoners, no torture. But you can assess for yourself the consequences of the drone program, in public data released by the Obama administration.

Earlier this month, the military concluded that 10 civilians — one of them an aid worker mistaken for a terrorist, and seven of them children — were killed in the Aug. 29 drone strike in Kabul. The Air Force’s inspector general will investigate.

So who was Bertha von Suttner? An ardent pacifist, she pushed Nobel to create the peace prize as part of his bequest. But Suttner was appalled when Henry Dunant, the founder of the Red Cross, became the prize’s first recipient, in 1901. Unlike Dunant, who focused on humanitarian aid in war, Suttner championed disarmament and ending warfare altogether.

About This Series

Gripped by the events in Afghanistan over the summer, we decided to launch Season Three with a careful consideration of what happened in the war and why — along with its impact on democracy at home. Plus, we wanted to offer some perspective on America’s bungled international interventions and national-building efforts across time.

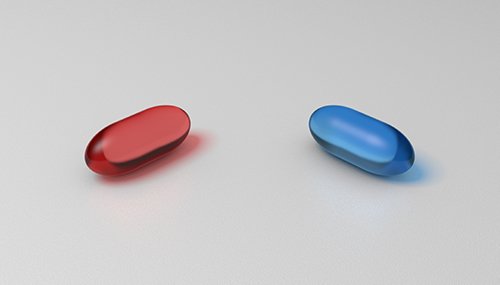

Inspired by Spencer Ackerman’s allusion to the 1999 thriller The Matrix, we’ve dubbed this series “Red Pill.” Fans of The Matrix will recall that Neo, the movie’s protagonist, is offered a red pill to escape the simulated world in which he’s trapped. So... just to clarify things, when Ackerman refers to having taken the “red pill” early on in America’s so-called war on terror, what he really means is that he initially took the comforting blue pill — and bought into a rhetoric of retaliation and national security at any cost. For this series, we’re using “red pill” in its original sense: a painful but much-needed dose of reality.