Hoover’s Ghost

He helped found the FBI, and his fingerprints are still all over the place.

Read

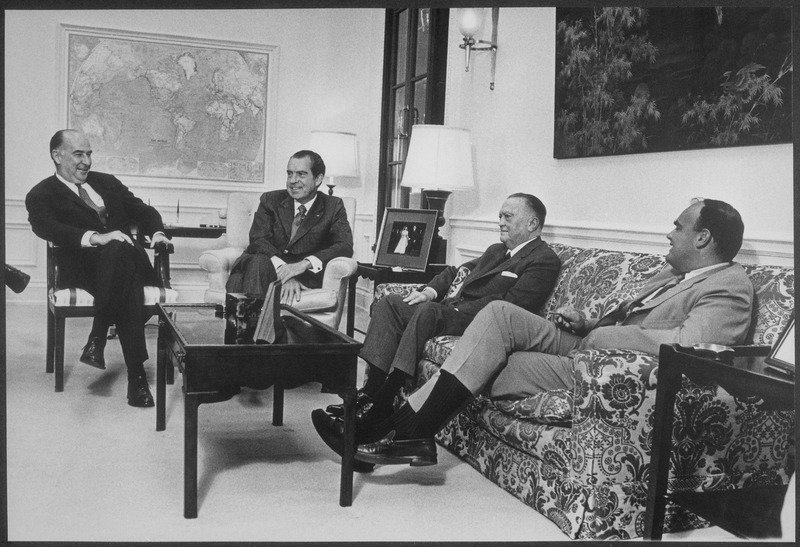

A consummate G-man, J. Edgar Hoover led the FBI for close to 40 years, becoming one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. Demanding rigor, loyalty and stealth from his subordinates, he worked closely with presidents of both parties, but his own views were steeped in conservative ideas on religion, race and anticommunism. Historian Beverly Gage considers Hoover’s legacy and helps us ask: Can the bureau he built effectively investigate a former president — and protect the republic?

As Gage tells Will and Siva, the ghost of Hoover still looms large, along with the attitudes and practices the late FBI director employed. Much of America’s contemporary surveillance state was incubated in Hoover’s bureau, where agents conducted investigations in the shadows, free from much oversight and divorced from partisan winds — except when they weren’t. Hoover saw his war on countercultural trends as a struggle for the core values that to him defined Western civilization. At the same time, he was not averse to wielding his own political power for, and at times against, the White House itself. While the old culture runs deep, Gage suggests, the bureau has an opportunity now to lean into its legacy of rule-oriented zeal which Hoover left behind.

Meet

Beverly Gage is the Brady-Johnson Professor of Grand Strategy and a professor of history and American studies at Yale University. Her research focuses on American governance, social movements and political ideology. She is the author of the new book G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Random House, 2022). Earlier she wrote The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in Its First Age of Terror (Oxford University Press, 2009). Gage is frequent contributor to the New Yorker, New York Times and Washington Post. Last year, President Biden appointed her to the National Humanities Council, which advises the National Endowment for the Humanities. Follow Gage on Twitter @beverlygage.

G-Man is perhaps the most comprehensive biography of J. Edgar Hoover to date. Gage chronicles Hoover’s reign over the FBI and the roots of his obsession with “religion, race and Reds.”

Published on the 90th anniversary of the 1920 bombing in Manhattan’s financial district, The Day Wall Street Exploded tells the hidden story of the hunt for those who carried out the attack, which killed 40 people and a horse. The likely culprits: Italian anarchists.

In March, Gage considered the world Americans inherited from the internationalism of Harry S Truman, who dropped two H-bombs on Japan but also helped create NATO and the United Nations.

Writing for Foreign Affairs last year, Gage reviews Louis Menand’s The Free World, which connects Cold War geopolitics with an explosion of cultural expression in the 1950s, as the United States tried to present itself as a model for the global community.

When former president Donald Trump tried to shut down the investigation into his ties to Russia by meddling with the FBI’s leadership, he was running the risk of inspiring another Deep Throat, Gage suggested in a 2017 op-ed. Go deep for yourself with more about FBI leakers and its internal politics, in a piece Gage wrote for the Journal of Policy History.

Read her thoughts on how to avoid democratic failure of the sort that rioters attempted to induce at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

It’s hard not to see the parallels between Hoover and Trump — both obsessed with conspiratorial thinking, both bent on amassing power. But the better comparison might be between Trump and Joseph McCarthy. Gage suggests that Trumpism, like McCarthyism before it, will live on as its proponents claim the mantle of political victimization.

In the mid-1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. received a typewritten letter accusing him of adultery, naming alleged lovers and suggesting he kill himself. He was sure it came from the FBI. As Gage wrote in the New York Times Magazine, it did.

Learn

For a good overview of the legal issues at stake in the U.S. Justice Department’s seizure of federal documents at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate, listen to national security expert Bradley Moss on the podcast Bloomberg Law.

In all, the government has reclaimed more than 300 classified documents since Trump left office, about half of which were returned voluntarily to the National Archives by his aides last January.

Trump has said that he declassified those papers — never mind whether any of them should have been carted down to Florida in the first place. But his lawyers aren’t using this line of defense in the courtroom. The New York Times explains when and how presidents may actually declassify government secrets.

In an unusual move, DOJ officials included in a court filing one photo of top secret documents strewn on the carpet in Trump’s office. The former president’s attorneys called the image “gratuitous,” but it went viral on the internet as observers tried to make sense of all the interesting acronyms on them.

Not long after taking office, Trump shook the hand of then-FBI director James Comey and reportedly said, “I really look forward to working with you,” then proceeded to insist on Comey’s “loyalty.”

Trump’s legal team has accused the FBI of planting some of the documents during its search last August. The response to those public claims, from the special master appointed in the case? Sworn declarations, please.

In 2016, the Brennan Center warned that Trump’s authority to spy on Americans would “dwarf” anything Hoover even dreamed of.

In the 1950s, Hoover’s FBI launched a notorious covert operation called Cointelpro, short for Counterintelligence Program. Its targets included, especially, left-leaning organizations and social justice movements. But the program also went after the Ku Klux Klan, the Minutemen and other hate groups. Watch the 2010 documentary Cointelpro 101.

The program remained in existence until coming under scrutiny in the 1970s. Investigative journalist Betty Medsger tells the story of the professor-activists who blew the lid on Cointelpro, in The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover's Secret FBI. Fifty years after that heist in Media, Pa., its perpetrators received accolades for the effort, which yielded 1,000-plus confidential records.

Revelations from the burglary led to a landmark congressional inquiry. Sen. Frank Church, a Democrat from Idaho, led the committee that identified systemic abuses at the FBI, in 1975 — three years after Hoover’s death. Download the entire final report of the Church Committee from the Internet Archive.

Getting his agents exempted from federal civil service rules — and the accountability that might have entailed — was an important coup for Hoover in the early days of the bureau, as Gage explains on the show. This administrative loophole persists throughout the American surveillance state: The Department of Homeland Security recently announced the creation of another exempted unit: the Cybersecurity Service.

Weird (and scary) fact: The FBI is perhaps the most unsung critic of 20th-century African American literature. In the 2015 book F.B. Eyes, author William J. Maxwell of Washington University digs up more than 14,000 pages of secret files that fixated on black poets and novelists, including James Baldwin. Agents even drew up plans to swiftly incarcerate influential black writers, in case of a “national emergency.”

Hoover’s fraternity, Kappa Alpha, was founded in 1865 and claimed Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee as its spiritual source.