No Good Reason

America incarcerated well over 100,000 people for years without cause.

Read

After the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, a racial panic took hold over the United States and its leadership. And President Franklin D. Roosevelt — otherwise known for the progressive policies of his New Deal — approved the mass removal and confinement of Japanese American families, on scant evidence of disloyalty. Our team discusses this shameful chapter in U.S. history, and its legacy, with a daughter of two erstwhile internees and one of the world’s foremost students of the era.

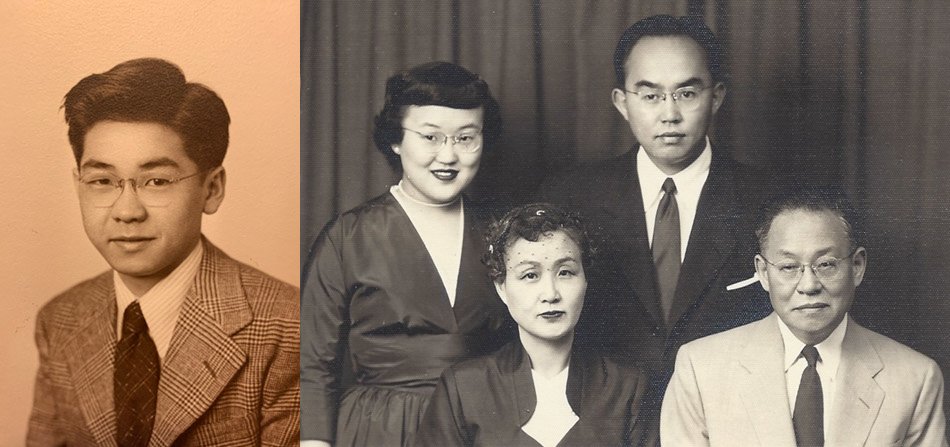

Education professor Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas and historian Greg Robinson help us explore the trials and paradoxes of Japanese American internment during World War II. As children, Inkelas’s parents were forced to leave California and live in “relocation centers” — really, concentration camps — in other states.

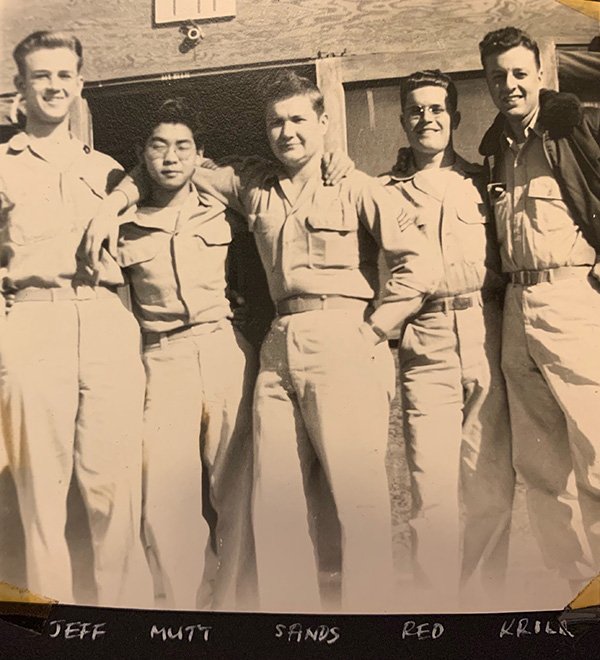

Like most of the 127,000 people interned for some three years, Inkelas’s parents were U.S.-born citizens. Before the war’s end, her father would have to don a uniform and face another relocation: to the Pacific theater. A generation later, Inkelas says, she would search for her roots in Japan, where she came to realize that identity is not as simple as where your family comes from.

Robinson has written for decades about the Japanese American experience, especially during and after the Good War. He calls Japanese confinement “a tragedy of democracy.” As he tells Will: “In a war fought for democracy, and the preservation of democracy against fascism, a democratic country and the leader of the forces for good in the world actually rounded up its own citizens, really out of no reason but wartime hysteria, political opportunism — very obvious flaws.” This, despite the fact that even J. Edgar Hoover’s notoriously paranoid FBI did not consider Japanese Americans a threat.

Meet

Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas is a professor of education at the University of Virginia’s School of Education and Human Development. She studies how college affects students, especially those from minority groups. Inkelas directs a project called Crafting Success for Underrepresented Scientists and Engineers, which tries to close the achievement gap in STEM fields. Her other research interests include living learning communities, mindfulness and the conditions for flourishing among first-year university students. She is the author of Racial Attitudes and Asian Pacific Americans: Demystifying the Model Minority (2006, Routledge).

Greg Robinson teaches history at the University of Quebec in Montreal. His work focuses on 20th-century America and he chairs the university’s research program on immigration, ethnicity and citizenship. Robinson is the author of numerous books, including By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (2001, Harvard University Press); A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America (2009, Columbia University Press); and After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (2012, University of California Press, 2012). He also writes a column, for Nichi Bei News, called “The Great Unknown and the Unknown Great.”

Writing for Nichi Bei in 2017, Robinson discusses the importance of complementing archival research with the first-hand accounts. He recounts many of Japanese American postwar stories in After Camp.

While most of the communities dislocated during World War II hailed from the West Coast, Robinson has also documented “the astonishing history of Japanese Americans in Louisiana,” in an edited volume from the University of Alabama Press. He has also written about the very cosmopolitan Japanese American Committee for Democracy, active in New York City in the 1940s.

In “Writing the Interment,” from the Cambridge Companion to Asian American Literature, Robinson contemplates the literary afterlives of internees.

Americans of African and Japanese descent joined forces in standing up against FDR’s Executive Order 9066, which allowed for wartime removal and confinement. These groups continued to work together in the civil rights era. But in an essay for the 2016 edited volume Minority Relations: Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation, Robinson examines how that relationship shifted from solidarity to tension, as Japanese Americans prospered after the war. In 1988, the government provided $20,000 in compensation for the living survivors of concentration camps. The United States has never made financial reparations to the descendants of enslaved people.

Developing a sense of belonging in college is a challenge for all incoming students. In a 2007 study, Inkelas found that this struggle is especially pronounced for students who belong to racial and ethnic minorities.

Asian Pacific Americans in particular “feel threatened by both majority and minority groups in the college admissions process,” Inkelas writes in the Journal of College Student Development. At the same time, in a longitudinal study of Asian Pacific American undergraduates, she found that their participation in ethnic clubs and activities deepened their group commitments.

In Racial Attitudes and Asian Pacific Americans, Inkelas observes that APA students generally receive less attention in scholarship on higher education because of their “invisibility” in policy discussions.

Learn

In the late 19th century, relations between Japan and the United States seemed cozy enough. In 1884, just two years after Congress had adopted the Chinese Exclusion Act — prohibiting Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States — America signed a treaty with Japan supporting Japanese immigration and naturalization.

Less than a decade later, sentiments had begun to change. The San Francisco school board moved to segregate Japanese and Chinese students from their white counterparts. In a diplomatic exchange from 1907 to 1908, American and Japanese officials outlined a “Gentlemen’s Agreement” in response. The administration of then–President Theodore Roosevelt agreed to pressure California leaders to end school segregation, while Japan committed to limiting the immigration of laborers.

Fueled by white nativism, the Immigration Act of 1924 would supplant that agreement. Also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, that law banned all immigration from Asian countries — a policy that would remain in place until 1965.

Living mainly in ethnic enclaves on the West Coast, Japanese Americans faced racist and exclusionary attitudes long before the government forced them to move. Among their nemeses: the U.S. labor movement.

FDR’s order allowed the military to open concentration camps in far-flung states: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. Download a complete map of confinement sites from the Japanese American National Museum.

A typist for the California Department of Motor Vehicles became an unlikely hero in the fight to end the government’s policy of internment. Mitsui Endo took her case to the Supreme Court and won — on Dec. 18, 1944. Still, splitting hairs, the court also ruled that mass removal itself had been constitutional, in the notorious case of civil rights activist Fred Korematsu.

Among critics of Japanese internment Eleanor Roosevelt stands out. While she never publicly criticized her husband’s decision to issue Order 9066, the First Lady privately pushed for closing the camps.

Tellingly, not a single Japanese American was convicted of spying or sabotage. Relocation and incarceration, meanwhile, proved to be an economic calamity destroying (in today’s dollars) some $3.64 billion of wealth they had achieved over decades, writes Alice George for Smithsonian Magazine: “Their businesses were hijacked by people eager to profit from their misfortune. As they prepared to reach the first stop in their odyssey — temporary detention centers — many were forced to sell property at bargain-basement prices.”

We asked both guests on this episode to compare current debates over migrants from Mexico and Central America with the history of FDR’s relocation centers. The Santa Barbara & Ventura Colleges of Law asked their students a similar question, in 2019. “The silenced history of those imprisoned after the bombing of Pearl Harbor is eerily similar to the separated families at the U.S. border today,” they wrote.

If you’ve been listening to the show since 2020, you know that humane immigration policy and resistance to xenophobia are crucial topics for us — and for saving democracy. Check out episodes like “Border of Cruelty,” “Census Division” and “Bittersweet Dreams” for much more.

Heard on the show

At the top of the show, you’ll hear a bit of Franklin Roosevelt’s famous address to Congress following the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor — “a date which will live in infamy.” Read the full text at the Library of Congress website.

We also scored the show with tracks from some of our favorite Creative Commons artists, in this order: Chad Crouch, with “Pacific Wrens” (2021); Pawel Feszczuk, with both “Monsters of the Past” and “A Chat by the Fire” (2022); Podington Bear, with “Lucky Stars” (2017); Kai Engel, with “Endless Story about Sun and Moon” (2015); HoliznaCC0, “Ugly Truth” (2022); and Lobo Loco, with “Pilgram Path” (2024). And, yes, it’s spelled Pilgram.

Transcript

Coming soon!